It is really wonderful to be part of a strong pottery community here.

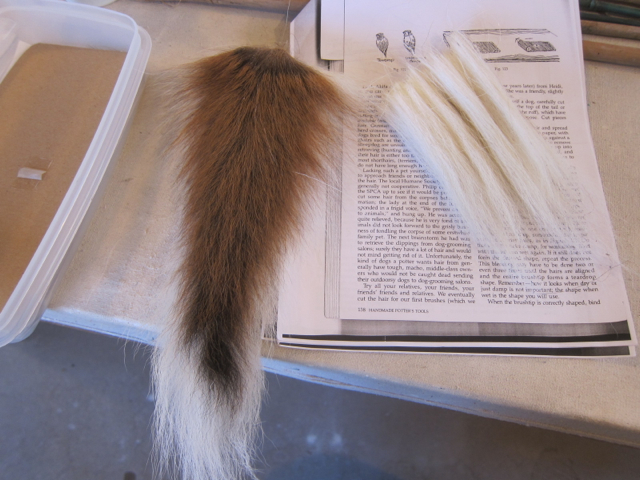

Everyone is so supportive of each other and I like being with all of them; so when I noticed that our farm cats here were leaving squirrel tails lying around their feeding area  (yes, our cats are better at actually catching squirrels than our enthusiastic but clueless dog), I asked Barbara Zaveruha if she would teach a brush-making workshop. My favorite liner brush is starting to wear out and I suspect it is made of squirrel hair or something similar.

(yes, our cats are better at actually catching squirrels than our enthusiastic but clueless dog), I asked Barbara Zaveruha if she would teach a brush-making workshop. My favorite liner brush is starting to wear out and I suspect it is made of squirrel hair or something similar.

Brushes Barbara has made.

My local women potter friends were invited and we convened in my studio one morning bearing various roadside finds and fur bits

to be converted into brushes for slip and wax.

to be converted into brushes for slip and wax.

I have a list of what you will need at the bottom of this post.

Step one is laying out the hair/fur. Set out a straight-edge of some sort and line your hairs up against it in a pretty thin layer.

Then begin at the end and pretend that the hairs are like a mat and roll them up.  The first hairs in line will end up at the center of your brush. Those will be the tip.

The first hairs in line will end up at the center of your brush. Those will be the tip.

Once you get a good shape, hold your bundle firmly and have someone (another good reason to make this a communal activity) wrap and then tie some dental floss around it where you want your brush to end.  This may be the middle of the bundle or closer to one end. Don’t worry how long the excess is, it will be trimmed later. Try to wrap a bit of a band.

This may be the middle of the bundle or closer to one end. Don’t worry how long the excess is, it will be trimmed later. Try to wrap a bit of a band.

What we discovered: coarse hairs should not be tied super-tight. Finer hairs like fox and squirrel hairs can be tied tightly, this does not deform the tip of the brush- but deer hair is much coarser and -my suspicions confirmed from some cursory research on the web– hollow. Which means the tighter we tied the wrap around it, the more it compressed and splayed outward giving us these frustrating multiple-tips results.

It suddenly came to me that we should try to tie it looser and Barbara assured us that later gluing would keep the hairs in place. A gently tightened but not tightly pulled wrapping yielded the first decent deer hair tip.

Notes on what hair to use from where: Barbara was using deer tail.  Colleen had some deer fur also; possibly from the belly or hindquarters? Not sure.**

Colleen had some deer fur also; possibly from the belly or hindquarters? Not sure.**

I took the longest hair I could find on our poor fox carcass and it was in the area behind the head, between the shoulders. This will work too, even if your only hair source is your (living) dog – apparently the Japanese prefer Akita hair for their best brushes so go ahead and call Fido over.

The fur/hair should have some kink or wave to it to hold the slip/wax/underglaze.

I don’t think curly coated dog’s hair will work nor the super-straight hair of say, a lab or pit bull (not long enough anyhow). I used the tip of a squirrel tail first and then the side hairs of the tail too- it all seemed to make a nice liner tip. Also, the finer hairs are probably best for smaller brushes and those larger thicker hairs better for big brushes.

Eventually we ran out of time, went in to eat soup and home-made bread (made by my talented husband) and scheduled a second workshop to finish the brushes. We all went off to boil our brush tips so they would be dry enough to clip and glue. This is a VERY IMPORTANT STEP because you don’t want your brush to reek after it has sat in water or worse, rot.

**********

We reconvened on a snowy morning with boiled tips in hand and proceeded to finish the brushes.

The boiling loosened the wrappings a bit so I ended up re-wrapping all the the ends and what I found worked best was about a ½ inch of wrapping to make the base of the brush a solid cylinder.

Barbara showed me a terrific type of knot. Before you start wrapping, you run a loop up that lays along the area you are going to wrap and just past it.  Then you proceed to wrap over the loop. When you get to the end of where you are wrapping, poke the string (or floss in our case) through the loop

Then you proceed to wrap over the loop. When you get to the end of where you are wrapping, poke the string (or floss in our case) through the loop  leaving a bit of looseness and pull on the other end of the loop- the end that is sticking out of the bottom of the wrapping where you started-pulling on it will pull the loop and other end of string under the wrapping; pull until it is about halfway down the wrapping and then cut off both ends.

leaving a bit of looseness and pull on the other end of the loop- the end that is sticking out of the bottom of the wrapping where you started-pulling on it will pull the loop and other end of string under the wrapping; pull until it is about halfway down the wrapping and then cut off both ends.

Next we trimmed non-tip end of the fur to a very blunt end  and then dabbed that end straight down onto a blob of glue and worked the glue up into the hairs.

and then dabbed that end straight down onto a blob of glue and worked the glue up into the hairs.  Sometimes we needed a second blob depending on how absorbent the hairs were. To compress the sides in- prevent flaring, we wrapped the end in tape but I did not tape 2 of the ends and that seemed to work too. You will have to judge which ends need the tape.

Sometimes we needed a second blob depending on how absorbent the hairs were. To compress the sides in- prevent flaring, we wrapped the end in tape but I did not tape 2 of the ends and that seemed to work too. You will have to judge which ends need the tape.

I had scrounged some bamboo pieces from our shed- formerly used to hold up plants. You can buy bamboo in varying thicknesses at garden supply stores . The narrow (usually green) I will use for my tiny liner tips and my two Fox brushes will go in thicker shafts.

Next you will have to drill out the right diameter in the bamboo. Look at the diameter of the bottom end of your brush tip and judge what thickness bit you need for your drill. It’s better to err on the side of too-small. As Barbara said, “you can always make it bigger.”

Where I chose to cut the bamboo shafts had to do with the “joint”. I wanted to have a good ¾ of an inch above the bamboo “joint” which provides a “floor” for the glue and brush tip to rest on.

The inside of the bamboo is soft and the joint floor is harder so your drill should sort of stop at the floor and if you don’t push really hard, you won’t go through it.

Barbara is holding the bamboo just below the “joint”.

Next try out your brush tip in the hole before you put glue in there! You may want to drill it out larger. Note: if your wrapping is nice and flat and not lumpy, you should be able to fit it inside the opening in the bamboo shaft. That’s why, when you are wrapping it, you want it to be tight and flat and very cylinder-like.

Note how different the end looks from when we first tied the bundles.

Note how different the end looks from when we first tied the bundles.

Once you can just squeeze the tip in, with possible help from the fettling knife to tuck a few stray hairs in remove it and put a decent sized drop of glue in there.

Re-insert your brush tip. Let dry and VOILA! You have a nice brush!

What you will need to make brushes:

- Fur with some waviness or kink to it but not curly hair. Squirrel, raccoon, deer or canine fur (fox, dog) is ideal.

- A straight edge of some sort.

- Dental floss or waxed string

- Water resistant glue- we used Duco, 5-minute epoxy would work too.

- Hair clippers are very helpful

- Fine saw

- Bamboo (from the garden store)

- A vice is very helpful

- Drill and variety of sized bits

- Paper plate for the glue (our glue started to dissolve a styrofoam tray I had)

- Fine scissors

- Tweezers can be helpful

- Fettling knife

- Needle tool

- Toothpicks for the glue

- Tape

** The best information I found on hair were fly-tying sites and blogs! I wish we’d read this excerpt before we started!:

“For example, the body of a deer has hollow hair, the tail is solid hair. The body hair of a calf is solid. Tails of all animals, like squirrel, woodchuck, calf, are typically solid. Solid hair typically is used for wings and tails. It stays compact and does not flare and is relatively hard to stabilize on the hook because it is slippery. Hollow hair is typically body hair and is used for wings or for spinning where you want it to flare. It is used for tails as well, but there you want to control the flare by thread technique. If you look at the typical hollow hair, i.e. deer, elk, caribou, antelope, it looks like a carrot, thick tapering to thin, with the thick part being hollow and the thinner part getting less hollow until it is actually solid at the tip. It is actually honeycomb hollow if you look at it under a microscope.”